‘The violence in particular scared many over what could happen if Somalia does not get its act together.’

In late April, after months of political tensions, forces loyal to Somali President Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed “Farmajo” exchanged gunfire in Mogadishu with those fighting for the opposition. The country teetered on the brink of all-out civil war.

The political crisis has come on top of a series of humanitarian disasters – the result of the long-running conflict with al-Qaeda linked insurgents al-Shabab, recent flash floods, and a predicted drought that, all told, will leave more than six million people in need of aid.

At the heart of the dispute has been Farmajo’s determination to stay in office for two years beyond the end of his term on 8 February, ostensibly to enable the holding of delayed elections. It was a move backed by the country’s lower house, but not the upper house, and a furious opposition – led by two former presidents – says the extension is simply a power grab.

What makes the situation so combustible is that the Somali National Army – despite years of donor-backed reforms – splintered along clan lines. Some units peeled off to support the Hawiye-dominated opposition, taking control of large chunks of Mogadishu. As many as 200,000 civilians fled the city, fearing the worst.

But this week could mark the beginning of a way out of the crisis. After intense domestic and international pressure, Farmajo agreed to abandon his term extension plan and instead allow Prime Minister Mohamed Hussein Roble to hold talks beginning today to broker a settlement.

Gathering around the negotiating table with Farmajo will be members of the opposition and the leaders of Somalia’s five federal member states. The goal is to build trust between deeply divided political rivals and move as quickly as possible to holding the delayed elections.

But the situation remains fragile. Last week, Farmajo rejected a role for the African Union’s special envoy, whose participation the opposition regards as crucial. Insiders say both government and opposition forces are on edge and could remobilise as quickly as they stood down when all sides agreed to summit talks.

“The recent political tension has only exacerbated the already alarming vulnerabilities faced by the people of Somalia,” Tareq Talahma, the head of the country office of the UN’s emergency aid coordination body, OCHA, told The New Humanitarian. “A peaceful resolution to the elections impasse, coupled with improved security, can only facilitate humanitarian action and ensure greater reach and support to people in need.”

The following provides an overview of Mogadishu’s political gridlock by explaining the main players who will be key to finding a way out of the crisis.

The Farmajo administration

When Farmajo came to power in 2017, he was hailed as a reformer. He had broken the political dominance of the Hawiye clan, and he promised the next election would be under a “one-person, one-vote” system rather than the clan-based, indirect ballots of the past.

But the goal of universal suffrage was undermined by both a lack of political agreement, and because much of the countryside is under the control of the violent jihadist group al-Shabab.

With the clock ticking, the federal government and member states agreed in September to a revised indirect vote system that would provide wider participation than previous elections. But that deal broke down, and subsequent efforts to rescue it failed, leaving Farmajo still in Villa Somalia – the seat of government – when his mandate expired.

Farmajo argues that the election delay wasn’t because he wanted to cling to power. Instead, he says it was the fault of clan-based elites unwilling to agree to reform a system that awards them immense influence – one that had also brought him to power in a notoriously corrupt poll four years earlier. He sees the opposition as vulnerable in a one-person, one-vote system.

A former US citizen, Farmajo is not from one of the dominant Mogadishu clans. He is a member of the Darod – a clan based in the southwest of the country.

Speaking on condition of anonymity, one ally of Farmajo’s who voted enthusiastically for his term extension told The New Humanitarian that the president’s supporters are the “silent majority” that live outside the capital.

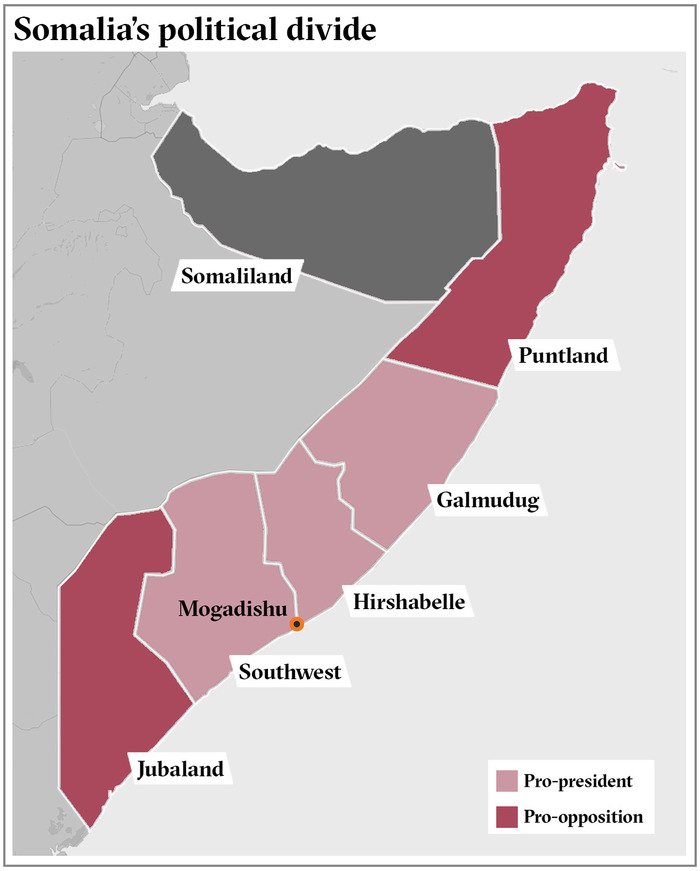

But the opposition says his presidency has been marked by what it considers to be grave overreach, including meddling aggressively in federal politics – which they say resulted in the installation by Farmajo of supportive leaders in South West, Galmudug, and Hirshabelle states.

When talks to resolve the crisis in early April collapsed, Farmajo and his supporters called for a special session of parliament on 12 April that agreed to his two-year extension – as well as theirs. It was the turning point in the political feud, and a move his opponents accused him of planning all along.

Although the upper house rejected the bill, it was signed into law – a step widely condemned by Somalia’s international backers. But Farmajo has rejected the criticism, while cultivating new alliances with Ethiopia and Eritrea, as well as with the influential Gulf states and Turkey.

The opposition

The opposition includes two former presidents – Sheikh Sherif Ahmed and Hussein Sheikh Mahmood – as well as an ex-prime minister, Hassan Ali Khaire.

These “recycled” politicians are far from “change” candidates, some critics charge, but they do have the backing of the Mogadishu-based Hawiye clan. The state presidents of Jubaland and Puntland have also joined them in a new political alliance, the National Salvation Forum.

The opposition argues that Farmajo is “the main obstacle towards peaceful, transparent and inclusive” elections. Their key demand is for him to hand power to an interim government.

But after security forces attacked hotels opposition leaders were staying in on 18 February, and then opened fire on a banned opposition march the following day, tensions rapidly increased. When parliament passed the mandate extension, Ahmed and Mahmood moved into fortified neighbourhoods of Mogadishu and the fear was they would declare a parallel administration, triggering a full-scale showdown with forces still loyal to the government.

The Prime Minister

After less than a year as prime minister, Roble is tasked with the most delicate of duties – overseeing negotiations to organise elections as quickly as possible.

In order to do this effectively, he needs all parties to believe he is impartial.

Roble has some advantages. He is Hawiye and, as a political newcomer, also has less troublesome baggage. That all factions of the army heeded Roble’s call to stand down and return to their bases is considered a sign that he has buy-in from the key players, at least for the time-being. But the situation remains fluid.

“The prime minister is the de facto ruler at the moment. He is given free rein to conduct the elections. He is also supported by the opposition and the international partners,” explained Mogadishu-based analyst Sakariye Cismaan. “So he is in a really good position unless he messes that up by not being tough on the president if [Farmajo] ever tries to pull something.”

The African Union

Last month, Farmajo called on the African Union to help mediate a way out of the crisis – a diplomatic intervention backed by the United States, the EU, and UN.

But a week before the start of Roble’s all-party negotiations, Farmajo rejected the AU’s nominated envoy – former Ghanaian president John Mahama – as being too close to his regional rival, Kenya. Feisal Omar/REUTERSOpposition forces muster in the Black Sea area of Mogadishu’s Hodan district, 17 April 2021.

Feisal Omar/REUTERSOpposition forces muster in the Black Sea area of Mogadishu’s Hodan district, 17 April 2021.

The African Union has 22,000 troops in Somalia under a peace enforcement mission known as AMISOM, defending the country against al-Shabab. It has condemned the extension of Farmajo’s term as “undermining [the] unity and stability of the country”, and called on AMISOM to “monitor” the deployment of Somali security forces while urging it to remain neutral.

“AMISOM is in a complicated position – it was designed to back the federal government in the fight against al-Shabab, but the current crisis in Mogadishu is a far cry from that,” said Omar Mahmood, senior analyst on Somalia with the International Crisis Group.

The opposition argues that AMISOM, in protecting Farmajo’s administration, unfairly legitimises it. “Any intervention during renewed fighting will be seen as partial to one or the other, while the cost of doing nothing can see the reversal of security gains,” Mahmood told The New Humanitarian.

The donors

Somalia’s Western partners have been criticised by the opposition for giving Farmajo a green light – or at least looking the other way – as he meddled in states’ affairs and politicised the security forces.

But the international community did quickly condemn the president’s extension plan. Key partners, including the World Bank, reportedly made it known they would pull the plug on funding, and that threat seems to have encouraged the search for a diplomatic solution.

“The violence in particular scared many [donor countries] over what could happen if Somalia does not get its act together,” said Mahmood.

The UN has welcomed this week’s summit and has urged all sides to participate to build much-needed confidence. “In addition, it will be essential that momentum is sustained once an agreement is reached,” Dana Palade, spokesperson for the UN’s Assistance Mission in Somalia (UNSOM), told The New Humanitarian in a written statement.

Somalia’s federal and state government are weak – dependent on international aid agencies working through local partners to deliver humanitarian relief.

The political gridlock has diverted what little attention tends to be paid to those critical humanitarian needs – which includes the close to 3.5 million people threatened by the worst drought in 40 years.

Hundreds of thousands of Somalis made homeless in recent years by either conflict or climate shocks shelter in overcrowded camps in urban areas, where they are vulnerable to any politically inspired violence.

“This obsession with politics, and inability to create an environment where all arms of government can fulfill their mandate, stagnates humanitarian interventions,” said Hodan Ali, director of a development unit in the Benadir Regional Authority, which includes Mogadishu.

Al-Shabab

The jihadist group has been content to let a squabbling political elite be their own worst enemy – characterising the small clique that rules the country as incompetent as well as corrupt. It has kept up its military pressure on government forces, triggering yet more displacement in the countryside

“The persistent political crisis gives al-Shabab an opportunity to sell itself as the reliable alternative for governance in Somalia,” said Hussein Sheikh Ali, a former government security adviser.

After two decades of battling the government, AMISOM, and Western special forces, al-Shabab still controls a large swathe of territory. It has not only proved resilient, but also adept at exploiting clan divisions. The expectation is that it will try to disrupt any upcoming elections through bombings and shootings – as it has done in the past.